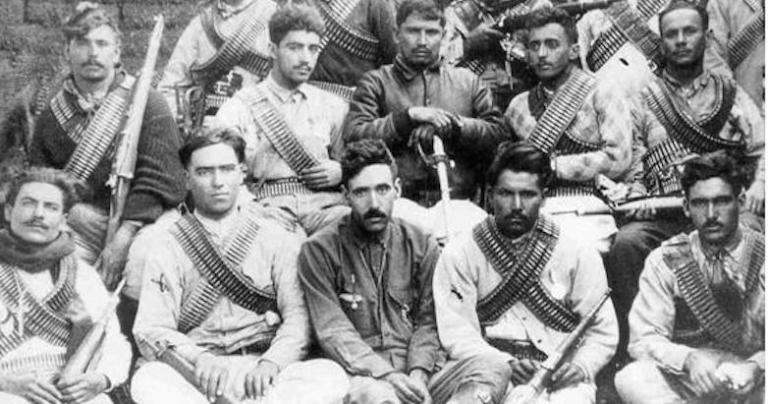

The Cristero War in Mexico envelopes one of the most turmoil events in Church history in this country. This violent example of political affairs with the Church was aggravated by rebels who stood to defend the faith that was attacked. It is said to have initiated Prior to Wolrd War under the direction of the Dictator Carranza. This persecution he initiated concluded in the expelling of many clergies and religious as well as hounding Bishop into the desert and doing sacrilegious acts with sacred objects and consecrated hosts.[1] From the side of witnesses such as the Knights of Columbus who to Mexico they also shared that they experienced after establishing themselves it happened that, "Just five years after the first Knights of Columbus council was established in Mexico in 1905, the country was catapulted into a long period of armed conflict, now called the Mexican Revolution. But what started as a fight against the established autocratic order evolved into a multi-sided civil war, with each competing faction claiming legitimacy."[2]

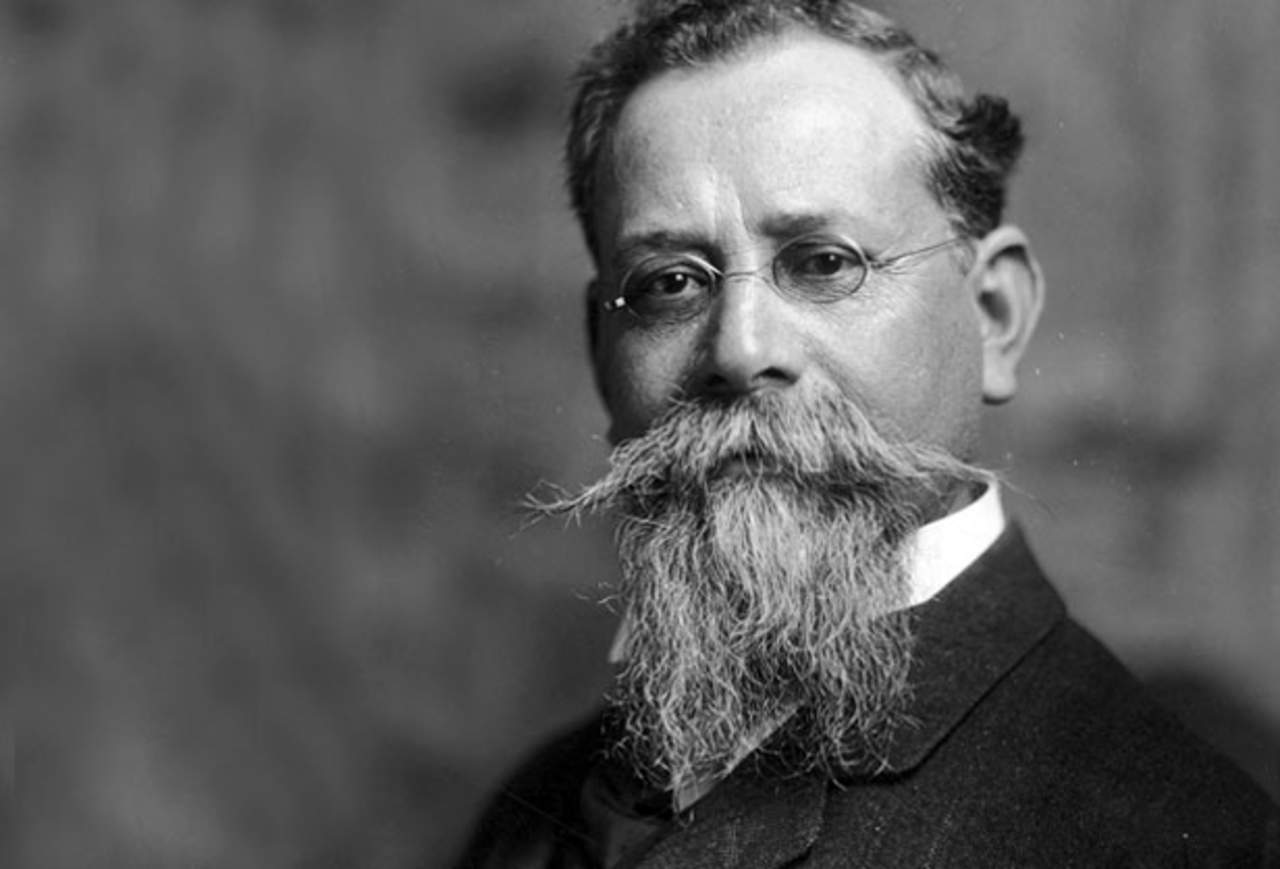

Moreover, this period of time as is acknowledged was on the rise of the Mexican Revolution that was to take effect. Thus, by, "1916 Venustiano Carranza called an assembly of delegates to draft a new constitution, and many of the delegates saw the church as an obstacle to social reforms. Thus the document they drafted, the Constitution of 1917, contained several articles that reduced the political, social, and economic power of the church. Among the many restrictions, clergy would no longer enjoy any special legal status, priests would now be considered members of an ordinary profession, and the number of priests allowed to reside in a given state would be limited. All priests in Mexico had to be native born, were required to register with civil authorities, and were prohibited from forming political parties. Religious ceremonies could not be performed in public; they were only allowed to take place within the confines of a church. Marriage was declared to be a civil, rather than a religious ceremony.

The Constitution also called for the establishment of a

primary educational system that would be free, obligatory, and most importantly,

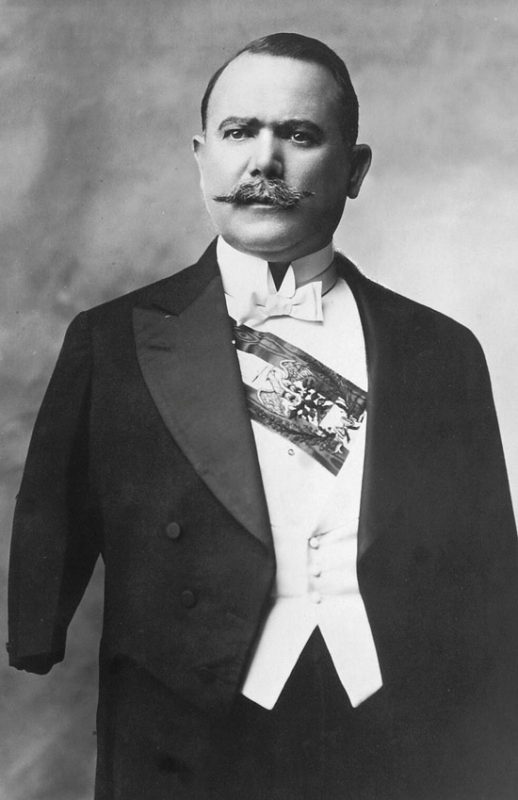

secular."[3] Amid this sitaution, there was to be the rise of a new type of power Communism in Mexico and in consequence Priests happened to be expelled and religious orders were suppressed under the government authority.[4] After the presidency of Carranza, the next person in power that succeeded him was Alvaro Obregon. It was Venustiano Carranza who, "did

not take very much action to enforce the anti-clerical articles, however during

Álvaro Obregón's administration hostility between the government and the Church

hierarchy increased markedly. Obregón expelled some Spanish priests from the

country as well as the Papal Nuncio, Monsignor Ernesto Filippi."[5] He did as well the blowing up of Shrines including the of the Virgin of Guadalupe and also Episcopal Residences.[6] It was not until the time of Plutcarco Elias Calles that the tension reached its peak. When he took office he declared himself, "an open atheist —

intensified the pressure. He decreed a huge fine (equal to $250 U.S. dollars at

the time) on any priest who wore a clerical collar, and demanded five years in prison

for any priest who criticized the government."[7]

By 1924 he did all that was at his reach to eliminate the Catholic Church the use of arrests, expelled and executing Clergy and Laymen. At the same time, he dismissed religious from Hospitals and insisted to teach lectures on atheism in school programs.[8] As a response to this the, "Catholic bishops called for a boycott against the government. Catholic

teachers refused to show up at secular schools. Catholics refused to ride

public transportation. Other civil disobedience occurred. The pope in Rome

approved the resistance. The government reacted by closing churches. Ferment

grew."[9]

Around the years of, "1926 and 1929, an

open rebellion took place against the government’s new persecutory laws, which

were formulated and strictly enforced under Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles.

Resistance to the “Calles Law” started peacefully, in the form of signed

petitions, economic boycotts and demonstrations. But in August 1926, sporadic

uprisings sparked the beginning of the Cristero War, or Cristiada. The rebels

took their name from their battle cry: “¡Viva Cristo Rey!” (Long Live Christ

the King!). To the Mexican government, this pronouncement often last words of

Cristeros before their deaths was more than a declaration of faith; it was an

act of treason."[10] Amid the great conflict, there were those who compromised their faith to be allowed to live. Such was a case of a Priest that apostate that was allowed to create a national Church with the design of maize, wafers and even agave juice.[11]

There were also at the same time the brave ones who stood their ground for their faith among the Cristeros were those clergies who died for the defense of the faith such was the case of Fr. Miguel Pro, a Jesuit pursuit by the government until he was caught and executed in 1927.[12] Another great example of heroism of martyrdom was the story of Jose Luis Sanchez del Rio. A boy 15 years old who became a symbol of laying down his life for his faith. It is said that, "José was born in 1913 in Sahuayo, Michoacán, México. He was the third of

four children. José loved his faith and grew up with a strong devotion to Our Lady

of Guadalupe. When José was twelve years old, the Cristero Wars began in

Mexico. During this period in history the Mexican government attempted to

extinguish the influence of the Catholic Church throughout the country.

It persecuted the Catholic Church by seizing property, closing religious schools and convents, and executing Catholic priests. In defense of the Church, the peasants of many of the central and western states in Mexico rebelled against the government. Even though he was too young to join the rebellion, José desperately wanted to be a Cristero and stand up for his faith. He begged his mother saying, “Mama, do not let me lose the opportunity to gain Heaven so easily and so soon.” He was eventually allowed to join the effort as a flag bearer. During a battle José was captured and was asked to deny his faith and the Cristero cause. José refused and was tortured terribly. Refusing to renounce his faith angered the government soldiers so much that they cut off the bottom of his feet. As José was forced to walk through town, he recited the rosary, prayed for his enemies, sang songs to Our Lady of Guadalupe, and proclaimed, “I will never give in. Vivo Cristo Rey y Santa Maria de Guadalupe!”[13] His act of heroism made him achieve his crown of glory, "St. José Sánchez del Río was beatified on November 20, 2005 and canonized by Pope Francis on October 16, 2016."[14]

It persecuted the Catholic Church by seizing property, closing religious schools and convents, and executing Catholic priests. In defense of the Church, the peasants of many of the central and western states in Mexico rebelled against the government. Even though he was too young to join the rebellion, José desperately wanted to be a Cristero and stand up for his faith. He begged his mother saying, “Mama, do not let me lose the opportunity to gain Heaven so easily and so soon.” He was eventually allowed to join the effort as a flag bearer. During a battle José was captured and was asked to deny his faith and the Cristero cause. José refused and was tortured terribly. Refusing to renounce his faith angered the government soldiers so much that they cut off the bottom of his feet. As José was forced to walk through town, he recited the rosary, prayed for his enemies, sang songs to Our Lady of Guadalupe, and proclaimed, “I will never give in. Vivo Cristo Rey y Santa Maria de Guadalupe!”[13] His act of heroism made him achieve his crown of glory, "St. José Sánchez del Río was beatified on November 20, 2005 and canonized by Pope Francis on October 16, 2016."[14]

[1] John Vidmar, The Catholic

Church Through The Ages: A History (New York/Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2014),

326.

[2] Maria de Lourdes Ruiz Scaperlanda, The Untold Story of the Knights During the Cristiada, (Columbia Articles and Columns: Article, 2012), at KOFC.Org, http://www.kofc.org/en/columbia/detail/2012_05_cristero_war_knights.html

[3] Elizabeth Garcia & Mike Mckinley, History of the Cristeada, (University of Texas: Article Blog, 2004), at utexas.edu, https://www.laits.utexas.edu/jaime/cwp5/crg/english/history/

[4] John Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through The Ages, 326.

[5] Garcia & Mckinley, History of the Cristeada, at utexas.edu, https://www.laits.utexas.edu/jaime/cwp5/crg/english/history/

[6] John Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through The Ages, 326.

[7] James A. Haught, The Cristero War – A

Catholic Rebellion Against an Atheist President, (The Good Men Project: Article Blog, 2018), at goodmenproject.com, https://goodmenproject.com/featured-content/cristero-war-sjbn/

[8] John Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through The Ages, 326-327.

[9] Haught, The Cristero War – A Catholic Rebellion Against an Atheist President, at goodmenproject.com, https://goodmenproject.com/featured-content/cristero-war-sjbn/

[10] Scaperlanda, The Untold Story of the Knights During the Cristiada, at KOFC.Org, http://www.kofc.org/en/columbia/detail/2012_05_cristero_war_knights.html

[11] John Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through The Ages, 327.

[12] John Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through The Ages, 327.

[13] Synodus Episcoporum, XV Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops: Young People, the Faith

and Vocational Discernment, Saint Jose Luis Sanchez del Rio, (Synod.va: Young Witnesses, Article Blog, 2018), at synod.va, http://www.synod.va/content/synod2018/en/youth-testimonies/saint-jose-sanchez-del-rio.html

[14] Angelus Staff, Cathedral Dedicates Chapel to Young Martyred Saint, (Angelus, Article Blog, 2019), at angelusnews.org, https://angelusnews.com/news/angelus-staff/cathedral-dedicates-chapel-to-young-martyred-saint

[15] John Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through The Ages, 327.

No comments:

Post a Comment