— JESUS NAZARENUS REX JUDÆORUM —

Diego Velázquez, Christ Crucified (cropped), 1632

" There are three sacred languages: Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, which are the most outstanding in the entire world. For in these three languages, the case of the Lord was written upon the cross by Pontius Pilate. For this reason, and on account of the obscurity of Sacred Scriptures, the understanding of these three languages is necessary so that you may reference one of the others if an expression in one of the languages presents some doubt to your mind about the meaning of a word or its interpretation. "

— St. Isidore of Seville, Etymologies, Book IX

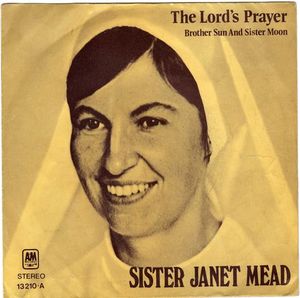

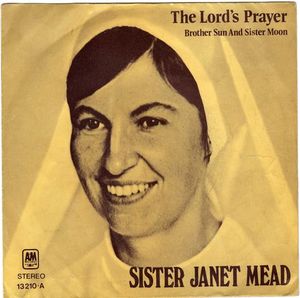

Sr. Janet & Pope John

In 2015, Sr. Janet Mead, of the Sisters of Mercy, was inducted into the South Australian Music Hall of Fame. Sr. Janet was made internationally famous for signing "The Lord's Prayer" – a pop rock setting of the English Pater Noster, which hit #4 on the Billboard's Hot 100 list during Holy Week of 1974.[1] (Which, anecdotally, was a big deal.) But how does all this appertain to a little-known Apostolic Constitution? To immediately clarify: this blog entry will certainly not be a tirade against the groovy music trending in 70's. Rather, our attention to Sr. Janet here is due to something she said during her 2015 induction speech, something which the reader might find rather curious, or, perhaps, rather common:

"In the 60's, a great change happened in the Church: Pope John XXIII stopped Latin being used—as it was, by that time, very unintelligible to the people, well, it had been before too, but we suddenly realized it. He said that the Mass should be much more reflective of people's lives so that they felt support in their prayer..."[2]

Cover of the 45 RPM picture sleeve for "The Lord's Prayer" Single by Sister Janet Mead, 1973

As an aside: Unfortunately, we cannot speak to her second claim (that St. John XXIII said "that the Mass should be much more... etc."), firstly, because this exceeds the limits of this present post, and, secondly, because this writer simply cannot find where Pope John XXIII may have said anything to this effect.* So much for the tangential.

Pope John XXIII: Latin's Greatest Enemy?

Returning to Sr. Janet's first point: Is what she says true? Did Pope John XXIII 'stop Latin being used' in the liturgy or otherwise? Ostensibly – depending on the hearers knowledge of ecclesiastical affairs – this claim could seem plausible: common knowledge would suggest that some time before and even into John XXIII's pontificate, Latin was practically the exclusive norm in the Church's** liturgies, ceremonies, and governance, and then, sometime after it, Latin all but disappeared from the Church. Well, if Latin has been suppressed in the Church, one will not find it in any of the pontifical acts of St. John XXIII. In fact, what one does find there, in the history of his pontificate, and indelibly written into the Acts of the Holy See, is his Apostolic Constitution Veterum Sapientia, On the Promotion of the Study of Latin, which stands directly opposed to any such claim that he may have done away with Latin, or that he could have even coherently entertained any sentiments ordered in such a direction.

Pope John XXIII, 24th April 1962

The Document Briefly Examined

If Pope Paul VI's encyclical letter Humanae Vitae is, as some say, the most rejected papal document of recent history (arguably of all time, depending on the parameters of the comparison) – some figures claim that, of "Western European and American Catholics, 80%... have themselves rejected the teaching of Humanae Vitae"[3] – then, perhaps, John XXIII's Apostolic Constitution Veterum Sapientia is the most ignored papal document of recent history—certainly of any Apostolic Constitution in recent history. At barely five pages long, the reader is mightily encouraged to read the document in full at their convenience—offering it as an act of reparation for the popular disregard it has hitherto received might even prove meritorious. Nonetheless, let us here briefly examine the document in question.

John XXIII begins by praising Greek and Latin, and "the other venerable languages, which flourished in the East,"[4] calling them "a vesture of gold," "in which wisdom itself is cloaked."[5] But, among these, he gives pride of place to Latin as "the rightful language of the Apostolic See."[6] He then recapitulates the conclusions of his predecessor, Pius XI, from his apostolic letter Officiorum Omnium, which:

"indicated three qualities of the Latin language which harmonize to a remarkable degree with the Church’s nature. For the Church, precisely because it embraces all nations and is destined to endure until the end of time… of its very nature requires a language which is universal, immutable, and non-vernacular."[7]

The Supreme Pontiff then explains how Latin so excellently fulfills each of these needs of the Church. Notably, he emphasizes:

"Of its very nature Latin is most suitable for promoting every form of culture among peoples. It gives rise to no jealousies. It does not favor any one nation, but presents itself with equal impartiality to all and is equally acceptable to all."[8]

Taken together with the fact that he he quotes Pius XII, who called Latin "a treasure... of incomparable worth"[9], and considering how valiantly Pius XII fought against the evils of warring nations during his own pontificate, this constitutes a strong case for the value of Latin as a force for unity. But Pius XII himself did not limit the value of Latin to its unifying aspect:

“The use of the Latin language prevailing in a great part of the Church affords at once an imposing sign of unity and an effective safeguard against the corruption of true doctrine.”[10]

To ensure that this great treasure would continue to endure – a treasure, again, which the Church "of its very nature requires," as Pius XI put it – John XXIII turned to the force of law: "We now, in the full consciousness of Our Office and in virtue of Our authority, decree and command the following:" (to mention but a few of his commands)

- "Bishops and superiors-general of religious orders... shall be on their guard lest anyone under their jurisdiction, eager for revolutionary changes, writes against the use of Latin in the teaching of the higher sacred studies or in the Liturgy, or through prejudice makes light of the Holy See’s will in this regard or interprets it falsely."[11]

- "No one is to be admitted to the study of philosophy or theology except he be thoroughly grounded in this language and capable of using it."[12]

- "The major sacred sciences shall be taught in Latin... Hence professors of these sciences in universities or seminaries are required to speak Latin and to make use of textbooks written in Latin. If ignorance of Latin makes it difficult for some to obey these instructions, they shall gradually be replaced by professors who are suited to this task."[13]

This is, to put it lightly, a tall order—but an order nonetheless. Yet so neglected was this papal document that people, such as Sr. Janet, could confidently say that John XXIII had, somehow, somewhere, legislated something to the exact opposite effect of what he had actually and solemnly promulgated for the good of the Church. The document was not, however, ignored by all. At end of his list of legislations, John XXIII added: "We further commission the Sacred Congregation of Seminaries and Universities to prepare a syllabus for the teaching of Latin which all shall faithfully observe..."[14] And this Congregation faithfully obeyed, producing the Ordinationes ad Constitutionem Apostolicam 'Veterum Sapientia' Rite Exsequendam.[15] Beyond this, however, few more if any obeyed, and now, according to the Veterum Sapientia Institute, "there are currently no seminaries or houses of formation at all that follow Veterum Sapientia and the Ordinationes to the letter."[16]

By an Unknown French master, Christ Teaching his Disciples to Pray, 13th c.

Veterum Sapientia and the Church Today

Surely, by now – contrary as it is to current practice – this document, or its pertinent parts, must have been suppressed, no? Well, as of yet, no, it has certainly not been, and – with the exception of the mandatory use of Latin in the Liturgy, presupposed at the time of its promulgation – it is, in fact, still entirely in force (so far as this author can tell)—though it is by no means enforced. Take, for example, the current Code of Canon Law, promulgated in 1983: Canon 249 states that: "The program of priestly formation is to provide that students not only are carefully taught their native language but also understand Latin well..."[17] Ironically, this English excerpt from the Vatican website is a poor translation of the Latin text of the Code: "linguam latinam bene calleant."[18] A better translation would be "well skilled," or even "well calloused" in the Latin language, not merely being able to understand it well.

As for the use of Latin in the Liturgy – a sensitive subject these days – it has certainly not yet been suppressed. Moreover, it should suffice to say that the Missale Romanum: Editio Typica Tertia and the Liturgia Horarum Iuxta Ritum Romanum are, as their names suggest, still promulgated (by the Latin Patriarch for the Roman Rite) in Latin.

— Laudetur Iesus Christus in Saecula Saeculorum —

_____________________________________________________

NOTES:

*In all sincerity, the author would appreciate being directed to such a statement of John XXIII, if it does, in fact, exist—but the author's assumption is that this can only be found appended to Pope John XXIII's suppression of Latin.

**To clarify, when we are here speaking of "the Church" and her use of Latin, the author is not referring to the other particular churches in communion with Rome, but to the Latin Church, under the Latin Patriarch.

WORKS CITED:

*An asterisk denotes that this source was found via the HACS Library

1. "The Hot 100," at Billboard, at https://www.billboard.com/charts/hot-100/1974-04-12/

2. SA Music Hall of Fame, "Sister Janet Mead - SA Music Hall of Fame Induction" at YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aoCmVcM7x0

3. *“Unholy Struggle with Third World Genie.” Lancet, vol. 342, no. 8869, Aug. 1993, p. 447. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(93)91584-9.

4. John XXIII, Apostolic Constitution on the Promotion of the Study of Latin Veterum Sapientia (22 February 1962), at www.papalencyclicals.net

5. Veterum Sapientia

6. Veterum Sapientia

7. Veterum Sapientia

8. Veterum Sapientia

9. Veterum Sapientia

10. Pius XII, Encyclical on the Sacred Liturgy Mediator Dei (20 November 1947), at vatican.va.

11. Veterum Sapientia

12. Veterum Sapientia

13. Veterum Sapientia

14. Veterum Sapientia

15. *Sacra Congregatio De Seminariis Et Studiorum Universitatibus: Ordinationes Ad Constitutionem Apostolicam ‘Veterum Sapientia’ Rite Exsequendam.” Revista Española de Derecho Canónico, vol. 17, no. 50, May 1962, pp. 435–60. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,cpid&custid=s9245834&db=lsdar&AN=ATLAiGFE171130001595&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

16. "Míssio," at Veterum Sapientia Institute, at https://veterumsapientia.org/mission/

17. Code of Canon Law, Can. 249, at vatican.va.

18. Codex Iuris Canonici, Can. 249.