Erasmus wrote his early sixteenth

century essay In Praise of Folly as a humorous work to amuse

him and his friend St. Thomas More. The essay is a piece of satire which mocks

nearly every segment of society; the uneducated classes; nobility;

and the intellectuals. Depending on which class of people Erasmus is

addressing, his tone shifts from comically bold, to irreverence, to

scorn. In Praise of Folly is not only social satire, however. It is a seminal commentary on the controversies within the Church during a period marked by turbulence and reform. In contrast with Reformation leaders like Luther, or Calvin, Erasmus does not attempt to initiate a schism with the Church by rejecting doctrine and forming a new Christian movement. Rather, his

essay condemns the excesses, corruption, and pretension among the

theologians and members of the Church's hierarchy during the era of, and preceding, the Renaissance, while maintaining personal allegiance to the Church.

In Praise of Folly

is narrated by Folly herself. She is brazenly proud as she calls

spectators to hear the case for why she, Folly, the quality of

foolishness, is most deserving of praise. The earlier passages of

Folly's speech have a far more jovial and humorous tone. She takes

responsible for bringing joy and pleasure to mankind; for granting

human continuity;1 for preserving marriages and friendships;2 for

allowing the arts and human activity to flourish;3 and for giving the

elderly delusions of youth.4 In contrast, she mocks the intellectuals who seek wisdom. While Plato thinks society should be ordered by philosophers, Folly claims they bring nothing but anguish and

misery to people.5

What makes In Praise of Folly such a pertinent commentary on the state of pre-Reformation religious affairs, without attacking Catholicism itself, becomes more apparent as Folly addresses contemporary religious behaviors. Her tone becomes noticeably less lighthearted and self-congratulatory than during the earlier part of the essay. The laity, monks, and hierarchy, are all subject to folly, just as anyone else. However, Folly describes their follies as ironically hypocritical, greedy, excessive, lavish, and harmful, rather than joyous, silly, or happy. The laity is superstitious;6 misdeeds are of no concern because forgiveness can be purchased; one will pray for every aspect of one's life, except to be saved from folly; and the priests encourage these ideas for profit. Theologians engage in convoluted and self-indulgent intellectual exercises, even reinterpreting sacred texts, without offering substantial explanations of doctrine for the laity.7 Monks obsess over minutia as a measure of piety, while also indulging in vices.8 Royalty care for their private interests, rather than the common good, virtue, or following God's wishes.9 Popes and bishops appear outwardly righteous, yet, in betrayal of apostolic piety, live in luxury, and wage war.10 These follies are quite different than the endearing attempts of elderly men to escape the reality of their age by concealing their baldness.

It would have been hyperbolic to generalize these corrupt and misdirected practices as though they were typical of the average layman, monk, bishop, or pope. However, Erasmus' essay must be considered in its proper context. Folly's narrative style is audacious, which contributes to the humor of the essay. Folly should not be considered the direct voice of Erasmus, since he wrote In Praise of Folly for amusement, rather than as a critical treatise. With that being said, corruption within the Church was nonetheless problematic. There were instances of corruption and improper behavior, including illicit sexual activity; bribery and lavishness; selling indulgences; and multiple benefices being held by one person for multiple salaries.11 Scholastic theology also suffered during the late Middle-Ages, as theological works became increasingly tortuous and convoluted.12

It is also notable that Erasmus' essay views Christianity positively, and lacks a secular underpinning. Moreover, unlike Luther, Erasmus does not criticize Catholic doctrine, nor considers it a cause of corruption. While Folly does take credit for Christianity, her tone is a positive appraisal of the efficacy of the Christian life in persuasion, happiness, and wisdom. Christ adopted the folly of humanness in order to help mankind.13 The Apostles were effectively convincing because of their miracles, not sophistic arguments.14 Through sarcasm, Erasmus praises apostolic piety as the proper mode of conduct for magisterium.15 The folly and madness of the pious give them a brief taste of Heaven, through which they experience a level of happiness which is otherwise elusive.16

I would recommend this work specifically for those who appreciate satire, history during the Reformation period, and, to a lesser degree, classical texts. Erasmus makes countless references to classic Greek and Latin culture throughout In Praise of Folly. If one is not familiar with classical works, the overall idea behind the essay is still intelligible, if not a bit obscured. However, one should be at least passingly familiar with the state of the Church during the Renaissance period, and the causes of the Reformation, in order to appreciate the humor and social commentary of the essay.

Like many timeless text, In Praise of Folly is readily available to read online, or download for free. Retail editions may include commentaries from the editors, or use different translations, however. The edition I used is John Wilson's translation, which is available as a free download at Christian Classics Ethereal Library's website at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/erasmus/folly.html.

What makes In Praise of Folly such a pertinent commentary on the state of pre-Reformation religious affairs, without attacking Catholicism itself, becomes more apparent as Folly addresses contemporary religious behaviors. Her tone becomes noticeably less lighthearted and self-congratulatory than during the earlier part of the essay. The laity, monks, and hierarchy, are all subject to folly, just as anyone else. However, Folly describes their follies as ironically hypocritical, greedy, excessive, lavish, and harmful, rather than joyous, silly, or happy. The laity is superstitious;6 misdeeds are of no concern because forgiveness can be purchased; one will pray for every aspect of one's life, except to be saved from folly; and the priests encourage these ideas for profit. Theologians engage in convoluted and self-indulgent intellectual exercises, even reinterpreting sacred texts, without offering substantial explanations of doctrine for the laity.7 Monks obsess over minutia as a measure of piety, while also indulging in vices.8 Royalty care for their private interests, rather than the common good, virtue, or following God's wishes.9 Popes and bishops appear outwardly righteous, yet, in betrayal of apostolic piety, live in luxury, and wage war.10 These follies are quite different than the endearing attempts of elderly men to escape the reality of their age by concealing their baldness.

It would have been hyperbolic to generalize these corrupt and misdirected practices as though they were typical of the average layman, monk, bishop, or pope. However, Erasmus' essay must be considered in its proper context. Folly's narrative style is audacious, which contributes to the humor of the essay. Folly should not be considered the direct voice of Erasmus, since he wrote In Praise of Folly for amusement, rather than as a critical treatise. With that being said, corruption within the Church was nonetheless problematic. There were instances of corruption and improper behavior, including illicit sexual activity; bribery and lavishness; selling indulgences; and multiple benefices being held by one person for multiple salaries.11 Scholastic theology also suffered during the late Middle-Ages, as theological works became increasingly tortuous and convoluted.12

It is also notable that Erasmus' essay views Christianity positively, and lacks a secular underpinning. Moreover, unlike Luther, Erasmus does not criticize Catholic doctrine, nor considers it a cause of corruption. While Folly does take credit for Christianity, her tone is a positive appraisal of the efficacy of the Christian life in persuasion, happiness, and wisdom. Christ adopted the folly of humanness in order to help mankind.13 The Apostles were effectively convincing because of their miracles, not sophistic arguments.14 Through sarcasm, Erasmus praises apostolic piety as the proper mode of conduct for magisterium.15 The folly and madness of the pious give them a brief taste of Heaven, through which they experience a level of happiness which is otherwise elusive.16

I would recommend this work specifically for those who appreciate satire, history during the Reformation period, and, to a lesser degree, classical texts. Erasmus makes countless references to classic Greek and Latin culture throughout In Praise of Folly. If one is not familiar with classical works, the overall idea behind the essay is still intelligible, if not a bit obscured. However, one should be at least passingly familiar with the state of the Church during the Renaissance period, and the causes of the Reformation, in order to appreciate the humor and social commentary of the essay.

Like many timeless text, In Praise of Folly is readily available to read online, or download for free. Retail editions may include commentaries from the editors, or use different translations, however. The edition I used is John Wilson's translation, which is available as a free download at Christian Classics Ethereal Library's website at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/erasmus/folly.html.

1. Desiderius Erasmus, In Praise of Folly. (Grand Rapids, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1958), 6-7.

2. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 11-12.

3. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 13, 15.

4. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 18.

5. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 14.

6. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 24.

7. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 34.

8. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 36.

9. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 39.

10. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 41.

11. John Vidmar, OP. _The Catholic Church Through the Ages_ 2nd ed. (Mahwah: Paulist Press, 2014). chapter 5, The Southern Renaissance, The Corruption of the Catholic Church. Ebook edition.

12. Alan Schreck. _The Compact History of the Catholic Church_, Rev. ed, (Cincinnati: St. Anthony Messenger Press, 2009), 67.

13. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 49.

14. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 34.

15. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 42.

16. Erasmus, In Praise of Folly, 52.

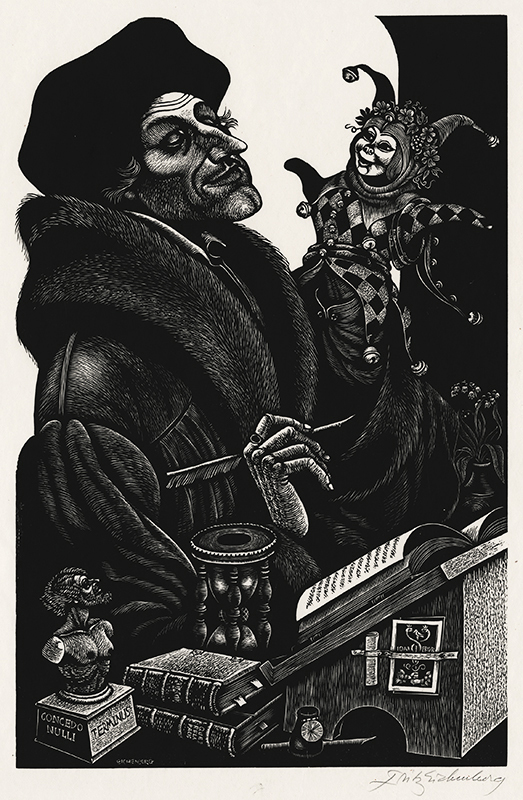

Image:

Fritz Eichenberg, The Human Comedy from "In Praise of Folly," (Aquarius Press, 1972), at annexgalleries.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment