Introduction: The Medieval era was a period notable for remarkable

development. Building upon the achievements and failures of previous centuries,

at this time, culture received numerous components that now remain at the core

of civilization. One area which benefited greatly from this growth was that of

the arts. Embraced within both ecclesiastical and political settings, artistic

expression took on a unique form during the Middle Ages, namely, illuminated

manuscripts. While it is difficult to date the birth of this artform, it is understood

that the tradition of using the codex (or book) began during the fifth

century, following the end of the ancient practice of writing on papyrus

scrolls.[1] Missionaries welcomed ornate

books as a means of educating the populace through beauty, while emperors implemented

illuminated manuscripts as tools to emphasize their absolute authority. This virtual

museum exhibit will discuss the connection between the cultural dynamic of the

Middle Ages and manuscript illumination, beginning with an exploration of this

specific art medium. An examination of the social development of this artform

will follow, illustrated by examples belonging to the Insular, Carolingian, Romanesque,

and Gothic styles.

The Making of Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts: During the Middle

Ages, the process of manuscript illumination was long and arduous. Produced primarily

in monastic settings, the pages of the earliest books were of vellum

parchment, a material most commonly made from the skins of sheep, goats, and

calves. To create a surface optimal for decoration, the animal skins were

soaked in lime for up to ten days, after which they were dried and shaped to

the desired thickness.[2] In addition, the

parchment-maker treated the skins with pumice powder and substances such as

bole and gum ammoniac, generating a surface receptive to ink and paint.[3] Paint was created from a variety

of elements, each blended with egg whites to form tempera. Gold leaf was

often applied, adding to the page's majestic appearance. The effect given by

the brilliant colors painted on the manuscripts, as well as the gold and silver

used in their adornment, led to the evolvement of its Latin name, “illuminare,”

meaning, “to light up.”[4] The completed book pages

were ultimately sewn together and placed in ornamental binding, covers which alluded

to the beauty held within.

The Cultural Development of Medieval Illumination:

Insular Illuminated Manuscripts

The first illuminated

manuscript example we will analyze belongs to the Insular tradition. The term Insular refers to manuscripts completed

in the British Isles from the seventh through the mid-ninth centuries.[5] While Insular art encompasses

the work of several British regions, our specific example is reflective of the

Celtic style. Beginning in the fifth century A.D., the Catholic Church strove

to Christianize the Celts, sending numerous missionaries to the Celtic region. As

Ireland embraced the Faith, monasticism flourished, together with the desire to

share the Gospel with Irish unbelievers. This ambition led to the development of

Celtic illumination. By supplementing their teachings with visual catechesis, the

missionaries who evangelized to the Celts added a remarkable dimension to their

education. The above image belongs to the Chi-rho-iota page of the

Book of Kells, a late eighth to early ninth century Gospel book believed to

have been illuminated at Iona, Scotland, or Kells in Co. Meath, Ireland.[6] Filling the page are the

Greek initials for Christ (XPI, Chi-rho-iota), with the partially abbreviated

words, autem generatio, placed at the bottom.[7] These words begin the narrative

of Christ’s life on earth, as this particular page leads to the event of Jesus’s

Nativity recounted in the Gospel of Saint Matthew. The designs comprising the Book

of Kells (as well as countless other Celtic manuscripts) recall the cultural

art of the region. In this way, the missionaries to the Celts evangelized using

artistic expression familiar to the surrounding tradition, all while placing God

at its center.

Carolingian Illuminated Manuscripts

In contrast to Celtic

illumination (art fully focused on the Divine), Frankish manuscripts of the

ninth century served a political purpose. Following the Fall of the Roman

Empire, the Western world was enveloped in a cultural drought, the effects of

which were felt keenly in the artistic realm. This situation, however, was

drastically transformed when Charlemagne ascended the Frankish throne in the

late eighth century. Charlemagne perceived himself to be a "new

Constantine,"[8]

and centered his reign around the arts, instituting a cultural revival which

became known as the Carolingian Renaissance. With the aid of influential minds

such as Abbot Alcuin of York, Charlemagne encouraged a growth in manuscript

illumination. This served a dual purpose. While educating all viewers,

Carolingian illuminated manuscripts simultaneously emphasized the authority of

the ambitious ruler. The above images of Christ in Majesty (left) and

Saint Luke (right) belong to the Godescalc Evangelistary, a manuscript illuminated

during the later years of Charlemagne’s reign. Created between 781 A.D. and 783

A.D. in Aachen, Germany, this manuscript carried both political and

spiritual significance. Commemorating Charlemagne's march to Italy, visitation

with Pope Adrian I, and the baptism of Pepin, his son,[9] this

manuscript emphasized the empirical power of Charlemagne, as well as the increasingly

significant role played by Catholicism in his reign.

Romanesque Illuminated Manuscripts

For a third example

of the relationship between manuscript illumination and Medieval cultural development,

we turn now to the Romanesque period. As society stepped into the eleventh

century, the artistic focus of Europe shifted toward a revival of ancient Roman

architecture.[10] However, manuscript illumination continued to look to the more recent past for

its inspiration, borrowing elements from the previous Insular and Carolingian

traditions. Illuminators in Romanesque Europe concentrated on the texts of Sacred

Scripture, encouraging piety through elaborate Bibles and Psalters. This artform

rested at the core of monasticism and was used principally within religious orders.

Consequently, it is of little surprise that these remarkable books were formed,

transcribed, and decorated within Medieval monasteries. The above images belong

to The Winchester Bible (1150-1175 A.D.), an English Romanesque

masterpiece. Containing in large format the complete Biblical text from the Book

of Genesis to Revelation, this manuscript was a “giant bible,” [11] a form of manuscript vital to monastic communities.

The main image offers us an excellent representation of the monumental size of

this book, as well as its intricate calligraphic text. Furthermore, the depiction

of the encounter between God and the Prophet Jeremiah which we find in the left-hand

detail ultimately exemplifies the merging of cultural artistic tradition that occurred

during the Romanesque period.

Gothic Illuminated Manuscripts

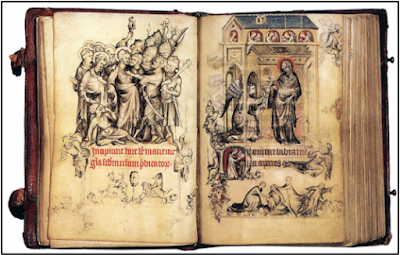

We now look to the

Gothic era for our fourth and final Medieval illuminated manuscript exhibit

piece. While still incorporating elements from the previous period, the Gothic manuscript

style acutely highlighted the time’s cultural growth. First and foremost, a revolutionary

focus was placed on the need for piety among all members of the Church, not

merely the religious. This mental shift experienced by European society

beginning in the mid-twelfth century led to notable growth in sacred artistic

expression. Catholic laity now became the creators and receivers of illuminated

manuscripts, and this branch of art was transformed to meet the needs of its

new category of recipients. Born from Gothic developments was the Book of

Hours, a devotion which became “medieval Europe's bestseller for three

centuries.”[12]

Whereas this manuscript template was adaptable, Medieval aristocrats and “ordinary

people”[13] alike were able to enjoy its

beauty. The above images depicting the Arrest of Jesus and the Annunciation

belong to the Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux, a fourteenth century Queen of France. Illuminated

in approximately 1325 A.D. by the French artist Jean Pucelle, this book conveys

the spiritual mindset surrounding the wide acceptance of devotion among the laity.

Presented by Charles VI, the "gift of the Book of Hours to his young wife

was intended to condition her behavior in a general way, to encourage her to

say her devotions regularly."[14] With plague and violence remaining

a constant threat, people of the Gothic period were compelled to seek

consolation in the Divine. They were thus inspired to pursue sanctity and found

sacred solace in the splendor of manuscript illumination.

Conclusion: The gradual development of Medieval manuscript illumination creates an illustration of the cultural

dynamic prevalent in the Middle Ages. As civilization adapted to the defining characteristics of each century,

so too did this artform. Beginning with the manuscript tradition of the seventh

century, this museum exhibit has followed the growth of this branch of art through

the centuries, leading to the style which would in time, give way to the Renaissance.

Although this artform eventually faded into memory with the

invention of printing, its cultural and religious significance has not disappeared. By examining the correlation between illuminated

manuscripts and the presence of Catholicism in the Middle Ages, it becomes

clear that the two are inseparable. After supporting each other throughout the

events of the Medieval world, both the Church and the tradition of manuscript illumination

continue to remain at the heart of sacred imagery, evangelizing viewers with

the Transcendentals of Goodness, Truth, and Beauty.

[1] Christopher

De Hamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts, (London: Phaidon Press

Limited, 1994), 9.

[2] "The

Making of a Medieval Book," (2003), in The J. Paul Getty Museum, at

www.getty.edu.

[3] "The

Making of a Medieval Book," in The J. Paul Getty Museum.

[4] "What

is an Illuminated Manuscript," in Khan Academy, at www.khanacademy.org.

[5] Carol

A. Farr, "Insular Manuscript Illumination," (August 28, 2019), in Oxford

Bibliographies, at www.oxfordbibliographies.com.

[6] Donald

W. Fritz, Origin and Meaning of Pattern in the Book of Kells," Journal

of Analytical Psychology 22, No. 4 (1997), 343.

[7] Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner's Art Through the Ages, Book B, Fourteenth Edition (Boston, MA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, 2013), 307.

[8] Nancy

Ross, “Carolingian Art, An Introduction,” in Khan Academy, at www.khanacademy.org.

[9] “The

Godesalc Evangelistary,” in History of Information, at

www.historyofinformation.com.

[10] Kleiner, Gardner's

Art Through the Ages, Book B, 334.

[11] Andreas

Petzold, "The Morgan Leaf from the Winchester Bible," (February 7,

2019), in Smarthistory, at www.smarthistory.org.

[12] Jonathan

Canning, "Colourful Devotions," Art Book 5, No. 2 (1998), 7.

[13] De

Hamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts,168.

[14] Joan

A. Holladay, "The Education of Jeanne d'Evreux: Personal Piety and

Dynastic Salvation in her Book of Hours at the Cloisters," Art History

17, No. 4, 585.

Image

Credit:

Image

1. "Eadwine

the Scribe, Canterbury Psalter,” Illuminated Manuscript, 1755 A.D., Trinity

College, Cambridge, www.royalacademy.org.uk.

Image

2. "Christ's

Monogram Page, Book of Kells," Illuminated Manuscript, c 800 A.D., Trinity

College, Dublin, http://culturedart.blogspot.com.

Image

3. "Christ in

Majesty, Godescalc Evangelistar," Illuminated Manuscript, 781 - 783 A.D., National

Library of France, Paris, https://higherinquietude.wordpress.com.

Image

4. "Saint

Luke, Godescalc Evangelistary," Illuminated Manuscript, 781- 783 A.D., National

Library of France, Paris, https://www.zvab.com.

Image

5. "God

addressing Jeremiah, The Winchester Bible," Illuminated Manuscript, 1150 - 1175 A.D., Winchester Cathedral Library, England, https://smarthistory.org.

Image

6. "Winchester

Bible," Illuminated Manuscript, 1150 - 1175 A.D., Winchester Cathedral Library, England, https://smarthistory.org.

Image 7. “Book of Hours of Jeanne d'Évreux," Illuminated Manuscript, c. 1324–28 A.D., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, https://www.wga.hu.

No comments:

Post a Comment