The life of St. Antony Abbot, Patriarch of Monks, comes down to us thanks to a certain man, one of a spiritual stature similar in immensity to that of his subject: St. Athanasius, Patriarch of Alexandria and Doctor of the Church. In his preface to the work, Saint Antony of the Desert, St. Athanasius explains that he composed this hagiography at the request of some monks who, laudably wishing to rival the sanctity of the monks of Egypt, sought to know more about this great saint, who preceded them and excelled so marvelously in religion, so as to imitate him. And rightly so, "for," as St. Athanasius puts it, "the life of St. Antony is to monks a sufficient guide to religious life"[1]. Now, St. Athanasius, though he was forty years the abbot's junior and readily admits that others new knew him better, having spent more time with him – and that he would have liked, had the seasons allowed, to have sent for some such monks in order to have given a fuller account – he, nonetheless, was well suited for this task of recounting the wonderful life of St. Antony. This is so, not only because he himself was thoroughly versed and practiced in the science of sanctity, and could therefore gaze upon Antony's life with eyes unclouded by the fog of human respect, but also because he had known the man personally and "was his assistant for no little time and poured water on his hands"[2]. As the reader shall see, the account he gives is amazing, and still he insists that he gives "but little account" of St. Antony—who's heroic life of continuous sacrifice would truly be beyond belief had Our Lord not assured us that with God all things are possible (Mt 19:26).

St Athanasius, by Francesco Bartolozzi after Domenichino, c. 19th century

If asked to summarize the life of St. Antony with a single verse of scripture – other than that which he took for himself, as we shall see – one might turn to the strong words of St. Paul: "I count all things to be but loss for the excellent knowledge of Jesus Christ my Lord; for whom I have suffered the loss of all things, and count them but as dung, that I may gain Christ" (Phil 3:8). Antony was a young man, around eighteen or twenty, when his parents died, leaving him with the care of his young sister and a sizable inheritance. He had been given a comfortable life—but to what end? One day, while walking to the church, he was meditating upon the rewards stored up in heaven for those who had left all things to follow Christ, and, when he had come to his destination, he heard the Gospel proclaimed: "If thou wilt be perfect, go sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come follow me" (Mt 19:21). Immediately, applying this word to himself, he went and sold all his inheritance, his land and his goods, giving the price to the poor, keeping only a small sum for the care of his sister. The next day, he likewise heard the words of Our Lord proclaimed: "Be not therefore solicitous for tomorrow" (6:34), and so he gave what little remained to the poor also, entrusting the care of his sister to a community of virgins. He then dwelt in the yard of his former home, praying, doing penance, and working with his hands to earn alms for the poor. From this point onward, he unceasingly strove to follow Christ with an ever increasing zeal.

This constant and ever growing zeal, if we understand it to be the exercise of charity through ceaseless prayer, may be said to be the the most important principle of St. Antony's religious life. He understood well that the Lord's favor can be lost in a moment of iniquity, even after a lifetime of righteous service (cf. Ezek 3:20), and so he resolved to live according to St. Paul's saying: "Forgetting the things that are behind, and stretching forth myself to those that are before, I press towards the mark, to the prize of the supernal vocation of God in Christ Jesus" (Phil 3:13-14). Thus, at all times, he could say also with the Psalmist: Nunc coepi, "now have I begun" (Ps 76:11). St. Athanasius calls this Antony's "strange-seeming principle," explaining that he "held that not by length of time is the way of virtue measured and our progress therein, but by desire and strong resolve. Accordingly, he himself gave no thought to bygone time, but each day, as though then beginning his religious life, he made greater effort to advance"[3]. This disposition of constantly beginning his service to God anew would be aided by two other indispensable dispositions in St. Antony's life: attentive listening and intense mortification.

St. Antony was no forgetful hearer (cf. Jm 1:25); indeed, it was his attentive listening that first lead him to discern his vocation during the reading of the Gospel, spurring him on to imitate the poverty of the Apostles. Moreover, "he so listened to the reading that nothing of what is written escaped him, but he retained everything, and for the future his memory served him instead of books"[4]. It was with this sort of rapt focus and a judiciously docile mind that St. Antony, in the first years of his religious life, searched for exemplars of Christian virtue in order to learn from them the way of perfection:

"If he heard anywhere of an earnest soul, he went fourth like a wise bee and sought him out; nor would he return to his own place till he had seen him and got from him what would help him on his way to virtue. . . He made himself really subject to the devout men whom he visited and learned for himself the special religious virtues of each of them: the graciousness of one, the continual prayer of another; he observed the meekness of one, the charity of another; studied one in his long watchings, another in his love of reading; admired one for his steadfastness, another for his fasting and sleeping on the ground; watched one's mildness, another's patience; while in all alike he remarked the same reverence for Christ and the same love for each other. Having thus gathered his fill, he returned to his own place of discipline and thereafter pondered with himself what he had learned from each and strove to show in himself the virtues of all."[5]

Living in this manner, St. Antony made great progress and was beloved by the townspeople, but he also drew the attention of one who was to be his lifelong nemesis: the devil, the infernal enemy of sanctity, could not abide such purity, especially in a young man, and so Satan began a war with Antony—one which he himself was confident he would win, but which he would, in fact, lose, battle after battle. He began to assail Antony with all manner of temptations: first to return to his family, wealth, fame, and relaxations, then to despond at the arduousness of virtue, the weakness of the flesh, and the lengthiness of time. But Antony overcame him with prayer. When this failed, surprised but undeterred, the devil began to molest the young man, day and night, by stirring his imagination and his passions against chastity, even appearing before him as a woman by night to deceive him. So great was the battle waged in the young Antony "that even onlookers could see the struggle that was going on between the two"[6]. But the young man was grieved at the thought of losing his nobility in Christ, and so, fasting and praying, he overcame the devil yet again. Having been cast out, and no longer able to touch Antony's mind, the enemy was enraged, and so he appeared before him visibly and spoke audibly, trying to flatter the man to pride by admitting his defeat. But Antony, thanking God rather than himself for this victory, mocked the vile creature, and the devil, filled with fear, fled before him. In this manner, Christ conquered the devil through St. Antony for the first time.

The Torment of Saint Anthony, attributed to Michelangelo, c. 1487

St. Antony knew well, however, that it would not be long before the enemy would return, for he is like a lion always waiting to strike (cf. 1 Pet 5:8). "He decided, therefore, to accustom himself to harder ways"[7]. And this is the next disposition of St. Antony, which would frame every aspect of his religious life: intense mortification. In fact, this would seem to be the whole practice of St. Antony: "For he said that when the enjoyments of the body are weak, then is the power of the soul strong"[8]. Explaining this, he taught: "A little time indeed we must of necessity allow to the body, but in the main we must devote ourselves to the soul and seek its profit, that it may not be dragged down by the pleasures of the body, but rather that the body be made subject to the soul, this being what the Saviour spoke of: ...But seek ye first his kingdom, and all these things shall be added to you (cf. Lk 12:31)"[9]. For this reason, St. Antony disciplined his body religiously, taking upon himself great penances:

"Such was his watching that often he passed the whole night unsleeping; and this not once, but it was seen with wonder that he did it most frequently. He ate once in the day, after sunset, and at times he broke his fast only after two days—and often even after four days. His food was bread and salt, his drink only water. Of meat and wine it is needless to speak, for nothing of this sort was to be found among the other monks either. For sleep a rush mat sufficed him; as a rule he simply lay on the ground. The oiling of the skin he refused, saying that it were better for young men to prefer exercise and not seek for things that make the body soft—rather to accustom it to hardships, mindful of the Apostle's words: When I am weak, then am I strong. (Cf. 2 Cor. 12:10)."[10]

This forma vitae, this way of life, was for St. Antony the school of the Cross, and when he had thus mastered himself, he departed alive into the sepulchers to dwell with God alone. There, at his request, a friend sealed him in a tomb, only bringing him some bread infrequently to sustain him. Here, again, St. Antony made battle with the devil and his apostate angels, who this time appeared as savage beasts and physically beat Antony, racking him with unbearable pains. Yet again, he overcame them by the grace of God and, after this ordeal, Christ healed St. Antony and spoke to him saying "I was here, Antony, but I waited to see thy resistance. Therefore since thou hast endured and not yielded, I will always be thy Helper, and I will make thee renowned everywhere"[11]. From here, at the age of thirty five, St. Antony departed into the wilderness, finding an abandoned fort to make his hermitage. Therein he stockpiled bread, and, going into the lower rooms, he anchored himself, praying to God in solitude and battling the demons, coming up for bread only twice a year and refusing to admit anyone. He lived this way for twenty years, and many sought to imitate him.

At last, his goodly friends, wishing to see him, broke down the very doors of the fort and carried them off. What then followed through the portal is astounding:

"And Antony came forth as from a holy of holies, filled with heavenly secrets and possessed by the Spirit of God. This was the first time he showed himself from the fort to those who came to him. When they saw him they marveled to see that his body kept its former state, being neither grown heavy for want of exercise, nor shrunken with fastings and strivings against demons. For he was such as they had known him before his retirement. The light of his soul, too, was absolutely pure. It was not shrunk with grieving nor dissipated by pleasure; it had no touch of levity nor of gloom. He was not bashful at seeing the crowd nor elated at being welcomed by such numbers, but was unvaryingly tranquil, a man ruled by reason, whose whole character had grown firm-set in the way that nature had meant it to grow."[12]

San Antonio Abad, Vicente López Portaña, 1794

From thence onward, St. Antony, now a true master of the religious life, began to teach others the way of perfection, and they all received him as their beloved father. "He too rejoiced to see the zeal of the monks and to find that his sister had grown old in her virginity and was herself a guide to other virgins"[13]. Much of St. Athanasius' work is dedicated to the teachings and counsels of St. Antony, but as we cannot quote all that is deserving – as it would constitute a reproduction of the book in full – we must let a single paragraph suffice:

"For all monks who came to him he always had this advice: to trust in the Lord, and love Him, to keep themselves from bad thoughts and bodily pleasures, and not to be led astray by the feasting of the stomach, (as it is written in Proverbs), to flee vainglory, to pray always, to sing psalms before sleeping and after, to repeat by heart the commandments of the Scriptures and to remember the deeds of the Saints, that by their example the soul may train itself under the guidance of the Commandments. Especially did he advise them to give continual heed to the Apostle's word: Let not the sun go down upon your wrath, and to consider that this was spoken about all the Commandments alike, so that the sun should not go down, not simply on our anger, but on any other sin of ours."[14]

Finally, after fifty years of teaching others the way of perfection, at the age one one hundred and five, St. Antony met his bodily death with the same serenity that had marked his earthly life and which would be his joy for ages unending. Wishing to die as he had lived, with God alone, he took with him only two companions, that they might bury his body in secret. With his final words, St. Antony counseled them one last time:

"Be you wary and undo not your long service of God, but be earnest to keep your strong purpose, as though you were but now beginning. You know the demons who plot against you, you know how savage they are and how powerless; therefore, fear them not. Let Christ be as the breath you breathe; in Him put your trust. Live as dying daily, heeding yourselves and remembering the counsels you have heard from me."[15]

He then instructed them to bury him in secret, and to distribute his three possessions: bequeathing his sheepskin garment and his cloak to Bishop Athanasius – who would come to be his hagiographer – and his second sheepskin to Bishop Serapion. Lastly he announced: "And now God save you, children, for Antony departs and is with you no more"[16]. They embraced him, then he, "gazing as it seemed on friends who came for him, and filled by them with joy, for his countenance glowed as he lay, he died and was taken to his fathers"[17].

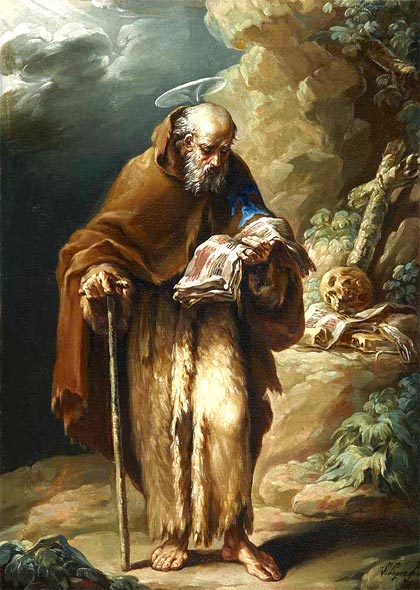

San Antonio Abad meditando sobre una calavera, Flemish School, c. 1600's

In this last bit, a reviewer is usually meant to either encourage or discourage the reading of the work in question. Given the excellence of the book presently at hand, however, this reviewer considers it something of an injustice to have even made the reader wait until the end to be so encouraged, for the reader would benefit far more from simply reading this small work for themselves than by giving time to this little summary—though the reviewer trusts that this has been edifying, nonetheless, as it simply recapitulates some of the works great points, like so few gems plucked from a magnificent crown. That being said, the reader is certainly and strongly encouraged to read Saint Antony of the Desert in full. This lucid biography, though not poetic, reads in part like something akin to an epic, as the indomitable champion of Christ overcomes the wiles of the devil and achieves spiritual mastery, and the rest reads like a letter from a father to his children, as that same aged champion now passes on his wisdom to the next generation of heroes. It is a swift, narrow stream, with deep waters and thunderous rapids, yet, in its midst, St. Antony stands unmoved and undisturbed, ever growing in virtue and grace as he contemplates God in the quietude of a soul made strong through discipline and love.

_____________________________________________________

1. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, in The Foundations of Western Monasticism, ed. William Edmund Fahey (Charlotte, NC: Saint Benedict Press, 2013), 13.

2. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 14.

3. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 20.

4. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 17.

5. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 16-17.

6. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 18.

7. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 20.

8. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 20.

9. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 46.

10. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 20.

11. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 23.

12. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 25.

13. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 51.

14. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 51-52.

15. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 72.

16. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 73.

17. Athanasius, Saint Antony of the Desert, 73.

No comments:

Post a Comment